‘State Of Silence’ Review: Vital Diego Luna, Gael García Bernal-Backed Film Documents Mortal Threat To Mexican Journalists

[ad_1]

A horror story is unfolding in Mexico, one written in blood and ink.

Since the year 2000, over 160 journalists have been murdered across the country. More than 30 others have disappeared and countless more have been threatened with death for simply trying to do their jobs – that is, to hold the powerful accountable.

This extraordinary reality comes into focus in the essential documentary State of Silence, directed by Santiago Maza and executive produced by Mexican stars Diego Luna and Gael García Bernal. The film, which premiered at Tribeca Festival in June, began streaming on Netflix on Thursday.

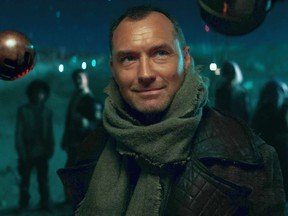

The film is built around the accounts of several investigative reporters who have been forced to go into hiding or even flee to the U.S. because of their work, including Jesús Medina, Juan de Dios García Davish, María de Jesús Peters, and Marcos Vizcarra. Medina upset the powers that be by reporting on illegal logging and mining operations in the Mexican state of Morelos, south of Mexico City.

Mexican journalist Jesús Medina in ‘State of Silence’

Netflix/La Corriente del Golfo

State of Silence shows closed circuit television footage of an incident in September 2017 in which Medina was approached by a man in a vehicle who told him, “You’re messing with the government, you son of a bitch. You’re going to get fucked.” Medina’s wife also got threats. She received a telephone call from someone who warned her to counsel her husband to take his investigative efforts “down a couple of notches.”

An American audience might assume, before seeing State of Silence, that the greatest threat to Mexican journalists would come from reporting on drug lords. Perhaps so, but what’s stunning about the film is the extent to which the amenazas come from those protecting the interests of elected officials. The film introduced me to a new term – narco-político, or narco-politics – meant to describe a state of affairs where the lines between politicians and traffickers have been blurred. Authorities and cartels are part of the same power structure that sees meddling journalists as a nuisance to be erased.

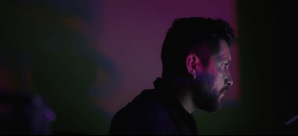

“There is a pact of impunity,” notes Vizcarra, who has reported on human rights abuses in Culiacán, in Sinaloa state. Thousands of people have disappeared there over a period of years, many chucked into mass graves, victims, presumably, of drug traffickers.

Mexican journalist Marcos Vizcarra in ‘State of Silence’

Netflix/La Corriente del Golfo

Vizcarra filmed an incredible shootout between elements of the army, municipal police and cartels in Culiacán that resulted in the deaths of 29 people, including 10 soldiers. At one point, his vehicle was seized and burned by gang of kids who said they had permission to kill him.

“It’s been a horrible day. My worst mistake was trying to report about what was happening,” he says in a live interview with a television station. “Doing my job was my worst mistake.”

There is a subset of people in Mexico and elsewhere around the world drawn by the urge to investigate and expose the conditions under which they and their neighbors live – to uncover wrongdoing, to implicitly point the way to a more just and equitable way of organizing ourselves. The tragedy – and it is not limited to Mexico, of course – is that this altruistic impulse can prove fatal.

It’s a sad testimony that things have reached such a dire state in Mexico that the government adopted a law in 2012 establishing a formal “Mechanism of Protection” for journalists and defenders of human rights. In the case of Medina and others in the film, the Mechanism did little more than pick up some expenses for them to go into hiding. Not exactly a lifesaver. In reference to the Mecanismo, Juan de Dios García Davish says, “You ring the panic button, and they don’t answer.”

Former Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, in office from 2018 to 2024, might have been expected to be a sturdy defender of the fourth estate, being a man of the left. But the documentary depicts him as hostile to scrutiny by journalists and willing, at best, to pay lip service to threats to reporters. One can only hope his successor, Pres. Claudia Scheinbaum, who took office at the beginning of this month, will prove more disposed to protecting journalists – but as a political disciple of López Obrador, that may be expecting too much.

‘State of Silence’

Netflix/La Corriente del Golfo

Stylistically, State of Silence departs from a strict “verité footage and news archive” approach in evocative ways. BEAK>, the English electronic rock group, composed an original score that conveys a menacing vibe, moving the tone from mere reportage to something more like to a political thriller. Maza incorporates a recurring visual motif – blood or dark sap that oozes down tree trunks, over thorny cacti and along dusty terrain, a metaphor for the spilling of blood and the inexorable seeping of corruption. Another recurring visual – a newsstand ablaze, orange flames shooting into a dusky sky – provides a stirring corollary to the journalists who describe what their calling has cost them.

Carmen Aristegui, the prominent Mexican journalist and news anchor whose fame may insulate her to some degree from risk, provides a coda to the film, addressing the stakes for a democratic nation where reporters routinely face mortal danger. “When you kill a journalist, you kill society’s right to be informed,” she says. “This needs to be stated over and over again.”